Apache Land

The Land

Or How Aravaipa Canyon Was Lost and Regained

By John Hartman

San Carlos Apache Reservation

Today the Camp Grant Massacre site belongs to over 100 descendants of Chief Capitan Chiquito Bullis, who are determined to conserve its natural beauty and preserve its historic and cultural integrity.

The lands along the Aravaipa were long an important seasonal settlement for the Aravaipa Apache. Traditionally, the lands were planted in spring and then harvested in summer.

Before the bands of Chief Ezkiminzin and Capitan Chiquito sought refuge at Camp Grant, their numbers had already been diminished by the battles at Aravaipa and at Mescal Creek and the Wheatfields.

The slaughter of their women and children on April 30, 1871 nearly made their roles as chiefs irrelevant. Not only had 120 woman and children been killed, but another 26 children were kidnapped and sold into slavery in Mexico. The loss of life threatened their groups’ ability to reproduce and survive.

Chief Capitan Chiquito struggled for the next 40 years to gain ownership of the land where his clan was almost eliminated and where the graves of his relatives were located. In spite of the fact the Apache Reservation had been relocated some 50 miles north, Capitan Chiquito was able to obtain permission to live and farm the land along Aravaipa Creek.

With the enactment of the Dawes Act in 1887, Capitan Chiquito was granted an allotment of 160 acres that included the gravesite of his murdered clansmen. This land was to be held in trust for Capitan Chiquito for 25 years by the U.S. Government, after which he could apply for a patent of ownership.

Capitan Chiquito’s patent was delayed due to accusations that he harbored the renegade Apache Kid in the canyon. The Apache Kid was a member of Capitan Chiquito’s band who was being sought for the murder of the Gila County sheriff. Because authorities were unable to find the Apache Kid, Capitan Chiquito and his family were taken prisoner and sent to Alabama where Geronimo and the Chiricahua Apaches were being detained.

After spending three years in Alabama, Capitan Chiquito and his family were allowed to return to Arizona. Upon his return, he had to deal with squatters who had moved into the area in his absence.

Capitan Chiquito spent the next 25 years of his life restoring his own spirit and resurrecting the spirit of the land by planting fruit trees and growing crops. Capitan Chiquito died in 1919 after acquiring influenza from other victims of the disease whom he had been caring for. Shortly after his death, the patent of ownership of this land was granted to Capitan Chiquito’s heirs. The land is presently owned by his direct descendants.

Since the death of Capitan Chiquito, the place where “the big sycamore is standing there” has gradually lost its human presence. For many years after Capitan Chiquito’s departure his relatives would return to the land for family gatherings and to collect herbs for food and medicine. The road from Old San Carlos to Aravaipa was heavily traveled by horseback and by those on foot. With the construction of Coolidge Dam in the 1930’s the Old Town was flooded and San Carlos was moved to its present site. When the automobile became the predominant means of transportation, the twenty mile road to Aravaipa that was traveled by horseback became inaccessible. The trip to Aravaipa is now about a 70 mile drive by automobile from San Carlos.

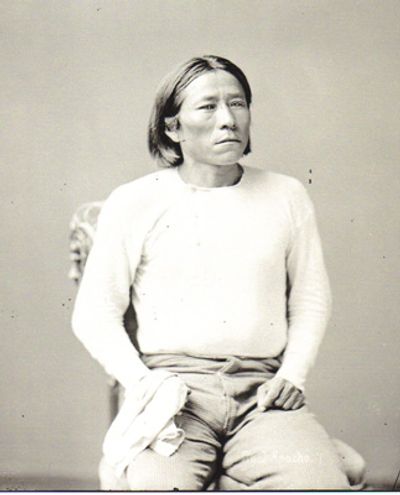

Chief Eskiminzen, 1876.

Chief Capitan Chiquito Bullis, ca. 1890s.

Last known photograph of Capitan Chiquito, here pictured as an older man with his wife and visitor at his Aravaipa homestead.

I love my land here at the Aravaipa Canyon and wish to live well and happy.

– Capitan Chiquito, 1901

He took us down there specifically to visit Aravaipa, to remember it – what he went through with the people living there. He told us a lot of stories when we were there, the good and the bad. He said, “That's good, graddaughter, you're here so someday you'll remember this – that you come from this, from my mother.”

Adella Swift on her visits to Aravaipa in the 1940s with her grandfather, Andrew Noline. Reported in Big Sycamore Stands Alone by Ian Record (p.56).

![]()

Chief Capitan Chiquito Bullis, ca. 1890s

“Our creation story tells us we are surrounded by four peaks – the sacred mountains...

There are songs from time immemorial about these mountains.”

Ramon Riley, White Mountain Apache elder. Quoted in Massacre at Camp Grant by Chip Chanthaphonh.

The History of the Aravaipa Apache

Early Period (Pre-Colonial)

(The following text draws in large part on Ian Record’s Big Sycamore Stands Alone, as well as Karl Jacoby’s Shadows at Dawn. Footnotes to come. As this is a work in progress, comments and feedback are especially welcome.)

Connection with the Land

The Apache, who call themselves Nnēē or the People, are made up of several groups. These include the Western Apache (to which the Aravaipa and Pinal Apache belong), the Chiracauhua Apache and the Warm Springs Apache. (The Ba Chi were those who left traditional Apache life for the Spanish missions.)

These groups are then divided into numerous bands, each of which takes its name from a particular geographic locale. In this way, Apache identity is closely woven with place. The Apache concept of Ni’ – or integration of the mind with the life force of the land – speaks to this deep connection.

Thus, the Aravaipa are known in Apache as the Dark Rocks People (after the black rocks of the Galiuro Mountains and Aravaipa Canyon). The closely related Pinal are known as the Cottonwoods Gray in the Rocks People (after the trees at the mouth of the San Pedro River).

All told, there are around 22 distinct Apache bands, all of whom are identified with a specific ancestoral landscape.

Origins

Because the Apache did not create permanent monuments or dramatically alter the landscape, few physical traces remain of their pre-colonial past.

Outside of origin myths and family narratives, what is known is that spoken Apache is related to other Athabaskan languages, like those of the Navajo and, further north, the Tlingit of British Columbia and Alaska.

It is for this reason scholars surmise that the Apache migrated to Arizona from the north, perhaps some time around the 15th century when the extensive Hohokam civilization all but disappeared.

By the early 1700s if not sooner, they had established settlements in the protective holds of southeastern Arizona’s mountain slopes, foothills and canyons. The Spanish called their territory, which stretched from the Mogollon Rim to the Natanes Plateau to the Gila River and the northern Catalinas, Apachería.

Societal Organization

Apache members trace their lineage through the mother’s line. In pre-reservation times family groupings (gotah) were led by a headman (and occasional headwoman), who organized the work and decided on seasonal migration.

Bands were made up of several gotah. Chiefs were chosen by the gotahheadmen, on the basis of their wisdom, wealth and generosity, skill, honesty and even temper. The chief was responsible for mediating disputes and coordinating activities.

In addition, the Apache maintained close matrilineal clan ties, which extended across bands and groups and helped to create networks of mutual support, as well as govern marriage and the use of farming sites.

Beyond the band was the major group. Allegiance was not by force but by choice. Large groups might come together to undertake major ceremonies or large-scale hunting parties.

Most of the time, gotah, bands and groups exercised a high degree of autonomy. In the often harsh and variable desert climate, this flexible social structure allowed families to adapt to changing circumstances, as needed.

Sustaining Life

In Apache communities, industriousness, generosity, honesty and bravery were valued as qualities essential to the group’s unity and survival.

Until their forced relocation to reservations, Apache lived by a combination of seasonal farming, gathering and hunting. Because of access to year-round running water, agriculture played a large role in Aravaipa and Pinal Apache life, with farms producing corn, squash and legumes in abundance.

Given the desert’s unpredictability, however, survival equally depended on collecting many different kinds of food, including mescal, acorns, berries, leafy greens, medicinal herbs and wild game. These were often found at great distances from the main farming settlements – and for only short periods during the year.

Therefore, after springtime planting, individual gotah would set off on gathering expeditions, as well as to hunt. (Even today, many San Carlos Apache continue to visit the northern Catalina foothills to collect acorns and the like.)

Fall was reserved for the harvest and the preparation of foods for storage, in time for winter.

Apache men dancing. Photo taken by Edward Curtis ca. 1906. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Copyright © 2019 Aravaipa Canyon Ranch - All Rights Reserved.